Posted July 4th, 2019 by Yorick

Devious Duke Frederick has usurped the kingdom of his older brother, Duke Senior, Duke Senior’s daughter Rosalind is allowed to remain at court—since she is the treasured confidante of Frederick’s only child, Celia.

Devious Duke Frederick has usurped the kingdom of his older brother, Duke Senior, Duke Senior’s daughter Rosalind is allowed to remain at court—since she is the treasured confidante of Frederick’s only child, Celia.

After a wrestling match in which a dashing newcomer defeats the local favorite, the victor, Orlando de Bois, falls head-over-heels for Rosalind. But the couple’s happiness will have to wait since the two must separately flee the court: he because his brother is trying to kill him and she because her uncle has grown annoyed with her growing popularity.

An exile in the forest of Arden, Rosalind disguises herself as a young man named Ganymede and Celia calls herself Aliena, sister to the youth. Along with them they take Duke Frederick’s court jester, Touchstone, one of Shakespeare’s wisest “fools.” Touchstone finds live in the forest with a dim-witted country wench named Audrey.

Into the same forest go Orlando and his trusty servant Adam. There they encounter Duke Senior and his merry men, and Orlando spends his days writing poetry to Rosalind. Soon “Ganymede” meets Orlando and playfully attempts to cure him of his lovesickness for Rosalind.

In the final scene, the whole company learns that a life of love, although filled with much folly—is indeed a life most jolly. Heigh-ho!

No responses yet. Leave one!

Posted June 25th, 2018 by Yorick

Two friends. Two girls. Two servants. Two cities. One great story.

Two friends. Two girls. Two servants. Two cities. One great story.

Lovesick Proteus stays in Verona to woo Julia while his best friend, Valentine, leaves for Milan to seek adventure. Not long after, Proteus’ father desires a similar experience for his son and packs him off to the Duke’s court in Milan amidst complaints from both Proteus and Julia. After many promises of continued love and an exchange of rings, Proteus reluctantly departs for Milan, where his friend Valentine has given his heart to the Duke’s daughter Silvia.

Nearly as soon as he steps ashore, Proteus too falls in love with Silvia—a situation that puts him in competition with his best friend for the lady’s hand. Unaware of this new rival, Valentine confesses all to Proteus: his love, the objection of Silvia’s father the Duke, and the couple’s plans to elope. Desperate to win Silvia’s affection, the treacherous Proteus alerts the Duke of the lovers’ plans while seeming to support his friend, and the enraged Duke banishes Valentine from the court.

Meanwhile, back in Verona, Julia decides to follow Proteus in order to be near him. Dressed as a page and calling herself Sebastian, she arrives in court just in time to see Proteus attempting to woo Silvia, who rebuffs him. Sebastian/Julia attaches herself to Silvia in order to keep an eye on the unfaithful Proteus.

Following his banishment, the languishing Valentine comes upon a group of outlaws who are themselves gentlemen cast out of court. They call for Valentine to be their king upon penalty of death. Back in Milan, Silvia enlists the help of Sir Eglamour to search for Valentine in the woods. The fugitive pair are attacked by the outlaw band when Proteus, the Duke, and Sebastian/Julia discover them. Proteus rescues Silvia from the outlaws and demands that Silvia repay him with her love. She flatly refuses just as Valentine arrives to inspect the outlaws’ captives. Humbled and genuinely sorry, Proteus apologizes for his rash behavior. Overcome by the situation, the page Sebastian faints; whereupon, the entire party recognizes Sebastian’s identity. Upon seeing her again, Proteus realizes that he truly loves Julia instead of Silvia. Witnessing the joy of the young lovers, the Duke assents to allow Valentine to marry Silvia and in the spirit of the day shows mercy to the outlaws. Valentine agrees to share his nuptials with his former rival and announces that they will also share, “One feast, one house, one mutual happiness!”

No responses yet. Leave one!

Posted July 10th, 2017 by Yorick

Resourceful, witty Viola is shipwrecked on the coast of Illyria. In the storm she lost contact with her twin brother, Sebastian, and believes him drowned. Needing employment, she disguises herself as a young manservant and with the help of the sea captain who rescued her, enters the service of Duke Orsino as a boy named Cesario.

Resourceful, witty Viola is shipwrecked on the coast of Illyria. In the storm she lost contact with her twin brother, Sebastian, and believes him drowned. Needing employment, she disguises herself as a young manservant and with the help of the sea captain who rescued her, enters the service of Duke Orsino as a boy named Cesario.

The Duke Orsino is in love with the Lady Olivia. He uses Cesario (Viola) as a go-between. But Olivia’s father and brother have recently died, so the lady remains sad and solitary. She refuses overtures of love from anyone, including Orsino.

Yet Olivia is impressed with Orsino’s sensitive young servant. She repeatedly asks Cesario to visit her. Soon she falls in love—not realizing the “manservant” is not a man at all.

Viola, for her part, has fallen in love with her employer, Duke Orsino.

The resulting love triangle is as confusing as it is hilarious: Viola loves Orsino; Orsino loves Olivia; Olivia loves Cesario (Viola).

Meanwhile, mayhem reigns in Olivia’s household. This comic subplot involves Olivia’s haughty steward, Malvolio; her uncle, Sir Toby Belch; a hopeful but ridiculous suitor, Sir Andrew Aguecheek; the servant Maria; and Feste, a jester. The motley gang convinces Malvolio that Olivia is secretly in love with him. A forged love note beseeches Malvolio to do several odd tasks to display his love. He enthusiastically obeys and hilarity ensues.

Viola’s brother arrives. Mistaking Sebastian for “Cesario,” Olivia asks the twin to marry her. Confused but charmed, he accepts, and they marry secretly. Soon “Cesario” and Sebastian appear together in the presence of both Olivia and Orsino to the company’s bewilderment. Viola finally uncovers her disguise and reveals that Sebastian is her twin. The play ends in several happy declarations of marriage.

No responses yet. Leave one!

Posted June 8th, 2016 by Yorick

In middle of the action with Desiree Talbert, Becky Greer Clements, Missy Workman Soltau, and April Thornton Peters

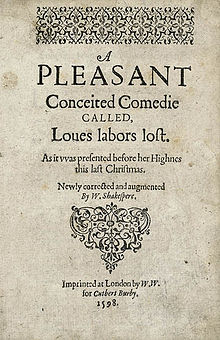

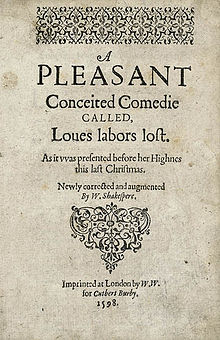

In 1995 Summer Shakespeare produced its first show, Love’s Labor’s Lost. Tickets were $1, and I was four months old. (Can we just take a minute to marvel at the fact that my parents started a theatre company with a newborn? And yes, when you start kids on Shakespeare that early, British spellings become second nature.)

Obviously I don’t remember much from that first summer, but over the last 21 years I’ve spent my summers exploring the forests of Arden, dancing with Midsummer sprites, and being perpetually embarrassed by my dad’s costumes (I’m still in therapy because of the Twelfth Night shorts of 2010!) In our family we remember dates by what play we did that summer. My brother Cole was born during The Importance of Being Earnest and I worked at camp in Hawaii during Love’s Labor’s Lost and Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Being a Summer Shakespeare kid means you do a little bit of everything. We’ve painted floors, shoveled rubber mulch, and sewed costumes. I’m in charge of making snacks for rehearsal (you can find my name in the program under “snack wench.”) Cole played the changeling child’s understudy in Midsummer Night’s Dream when the baby originally cast in the role wouldn’t go on. I actually cried of embarrassment after attempting to paint flowers on a prop suitcase for Two Gentlemen of Verona—needless to say, I did not get my dad’s artistic genes. We know how to run lights and sound (and by “we” I mean Cole) and we got our start in the business world ordering and selling cupcakes and bottled water. A little boy in the audience once asked his mom if he could get a cupcake from “Shakespeare’s daughter”—and I answered to it.

But the greatest lesson I’ve learned from Summer Shakespeare is something you’ll probably hear my dad say at the beginning of every show (if my mom remembers to write it on his cue card). “Laughter is the best medicine.” There’s nothing like seeing the smiles on faces of all ages after a show and knowing that the long hours of rehearsal and costume runs to Goodwill were all worth it. Because for an hour, our audiences experience “a brave new world,” and they end up loving it.

The most common comment I hear from people after shows is, “Your dad is hilarious. I bet you all just laugh all the time at home.” They’re absolutely right. While the rest of the world hits the beach, at our house summer means Shakespeare. And that’s just as we like it.

—Margaret Stegall

2 responses so far…

Posted June 23rd, 2015 by Yorick

Honorificabilitudinitatibus comes from a Medieval Latin word that roughly translated means “the state of being able to achieve honors.” Shakespeare uses the word only once in all of his works—in Love’s Labor’s Lost. (It’s not the sort of word or meaning that comes up often in casual conversation!) Honorificabilitudinitatibus is also the longest word in the English language featuring only alternating consonants and vowels. The word appeared in print as early as an 8th-century grammar book and as recently as a 2011 children’s novel.

Honorificabilitudinitatibus comes from a Medieval Latin word that roughly translated means “the state of being able to achieve honors.” Shakespeare uses the word only once in all of his works—in Love’s Labor’s Lost. (It’s not the sort of word or meaning that comes up often in casual conversation!) Honorificabilitudinitatibus is also the longest word in the English language featuring only alternating consonants and vowels. The word appeared in print as early as an 8th-century grammar book and as recently as a 2011 children’s novel.

Love’s Labor’s Lost itself is a “feast of words,” and the verbosity of several characters provides fodder fit for a word gourmand of the first order.

Costard the swain and Don Armado, a “fantastical shepherd,” both enjoy using big words and often do so to ridiculous, if not disastrous, effect. Early in the play Don Armado engages Costard to deliver a love letter. The Spaniard gives Costard a coin, telling him, “There is remuneration.”

As Costard gazes at the money, he discusses the coin and the word with himself until one wonders whether Costard values the word or the coin more:

Now will I look to his remuneration. Remuneration!

O, that’s the Latin word for three farthings: three

farthings—remuneration.—’What’s the price of this

inkle?’—’One penny.’—’No, I’ll give you a

remuneration:’ why, it carries it. Remuneration!

why, it is a fairer name than French crown. I will

never buy and sell out of this word.

So it seems apt that Shakespeare places honorificabilitudinitatibus in the mouth of the logophile Costard. When Costard overhears Don Armado and Holofernes (Holofernia in our play) prating on in Latin, he brandishes some Latin of his own, telling Moth, Armado’s juvenile page,

I marvel thy master hath not eaten thee for a word;

for thou art not so long by the head as

honorificabilitudinitatibus: thou art easier

swallowed than a flap-dragon.

(Of course, this raises the question of what a flap-dragon is. Evidently, it was both a game in which players snatched raisins out of a dish of burning brandy and tossed them, ablaze, into their mouths and said flaming fruit. This was big fun pre-technology.)

With 27 letters, honorificabilitudinitatibus lags only one letter behind antidisestablishmentarianism, the longest non-coined, nontechnical word in English and seven letters behind Mary Poppins’ celebrated supercalifragilisticexpialidocious coinage.

But wait! There’s more. The longest word ever to appear in literature was coined by the Greek playwright Aristophanes to describe a horrific-sounding fricassee of fish, birds, and sauces. The transliterated word is 183 letters long, hence its not appearing here.

The longest published word is 1,909 letters long and is, not surprisingly, a chemical name. The absolute longest word in English (another preposterous chemical atrocity) is purported to be 189,819 letters long. But the word doesn’t appear in any dictionary. Not much honorificabilitudinitatibus in that.

No responses yet. Leave one!

Posted June 7th, 2015 by Yorick

folio page

King Ferdinand of Navarre and his three friends, Berowne, Longaville and Dumaine, all swear to three years of diligent study. They further swear to abstain from all ordinary distractions like excess food and sleep during that time. In particular they pledge to avoid the company of females, keeping only a fantastical Spaniard named Don Armado and a country clown named Costard to entertain them.

Almost as soon as the four men sign the vow, Berowne remembers that the Princess of France and her three ladies, Rosaline, Maria, and Katharine are headed to Navarre’s court to collect a loan.

Meanwhile, Don Armado has fallen in love with the country maid Jaquenetta, who has an affection for Costard. When Costard is arrested for breaking the king’s edict about no female socializing, jealous Armado has Costard arrested by Dull the constable.

The ladies arrive, but the King will not allow them inside his house for fear of being forsworn, or breaking his vow. Disgruntled, the Princess and her entourage must camp in the field while they await missing papers regarding the loan. The delay gives the King and his friends time to fall in love with the ladies.

Elsewhere on the King’s estate, Don Armado frees Costard on condition he deliver a love letter to Jaquenetta. Soon after Berowne gives Costard a letter to Rosaline. In classic comedic style, the two secret letters get mixed up.

One by one the men are overheard declaring their love each for his lady. The men decide to disregard their sworn oath and woo the ladies with dancing, pageantry, and disguise. They costume themselves as Russians, but the ladies’ servant Boyet has warned the Princess of the trick. The ladies disguise themselves to foil the men’s silly plan. When the shifty-looking Muscovites enter, each woos the wrong woman. The confused Russians leave, and when the men return, the ladies mock them but soon succumb to their charms.

Don Armado recruits the schoolmaster Holofernes, Costard, and the page Moth to present the Nine Worthies—historical and legendary persons who personified chivalric ideals—as entertainment to the couples. The hilarious mood changes suddenly when Marcade brings news of a death in France.

As the ladies prepare to leave, the men insist that their love is genuine. The ladies challenge the lords to perform certain tasks for a year and a day before marriage can be considered. The lords agree with oaths to abide by the ladies’ wishes.

No responses yet. Leave one!

Posted August 28th, 2014 by Yorick

With its royals and lovers and fairies (oh my!), Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream has long been a favorite comedy for thespians and theatregoers alike. The obvious contrasts among the Athenian royalty, woodland sprites, and common laborers and the fusion of song, dance, and lyrical language—“I know a bank where the wild thyme blows,/Where oxlips and the nodding violet grows” (Act I, Scene 1)—make viewing the play a feast for both eyes and ears.

With its royals and lovers and fairies (oh my!), Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream has long been a favorite comedy for thespians and theatregoers alike. The obvious contrasts among the Athenian royalty, woodland sprites, and common laborers and the fusion of song, dance, and lyrical language—“I know a bank where the wild thyme blows,/Where oxlips and the nodding violet grows” (Act I, Scene 1)—make viewing the play a feast for both eyes and ears.

Shakespeare scholars date the play’s writing anywhere from 1590 to 1596, with most settling at the latter end of that time frame because of references to a wedding poem written by Edmund Spenser and published in 1595.

Several theories surround the creation of the play: Some believe Midsummer was written to celebrate a noble wedding; others conjecture that Shakespeare penned it to honor Queen Elizabeth I. (“Fair Vestal, thronèd by the West,” [Act II, Scene 1] refers to a beautiful virgin seated on a throne in the Western Hemisphere—who could that be?) But, alas, history can neither confirm nor deny this speculation

The form of Midsummer is in many ways similar to a masque, a pastime enjoyed among the aristocracy of Shakespeare’s time. Indeed, the play affords opportunity for elaborate costumes and sets as well as dramatic spectacle throughout the court and the forest.

But the play is more than frivolous revelry. We laugh at the characters’ folly yet relate in ways that transcend the humor. At the play’s beginning Lysander sighs, “The course of true love never did run smooth.” Truer words were never spoken, say we, the audience. Add to that the imbalance in the four lovers’ attractions—she loves him, he loves another, then both love one . . ., and it’s a rough ride to say the least.

The pixie world fares no better as Oberon and Titania spar over the changeling boy. These lovers’ quarrels and the decidedly incongruent pairing of ethereal Titania with ass-headed Nick Bottom all display romantic situations out of joint. Shakespeare explores the tangled mess with an air of fond amusement and good-natured rib-poking. And we connect with the Bard because we see in these absurd dilemmas our own love foibles.

A second audience connection is in the function of magic in the play. Puck’s ineptly applied charm in the form of a floral potion causes heartbreak and chaos—and a lot of hilarity—but also finally restores balance to the young lovers. The mischievous fairy’s vocal antics and head transplant trick intensify the enchanted quality of the play. Our sympathies are aroused as we see our own longing for an easy remedy for love’s trials: If only, we think, there really were an elixir of love. . . .

Finally, where would the play be without the dream of the title? Seven of the main characters use the word dream to describe the adventure’s otherworldly goings-on. The lovers view dreams as a natural effect of love, a “customary cross” (Act I, Scene 1) to be borne. Hapless Bottom utters it six times in one brief, bewildered (and bewildering!) speech. It is here that Shakespeare borrows, with egregious misspeaks, from the King James Bible, as Bottom blunders, “The eye of man hath not heard, the ear of man hath not seen, man’s hand is not able to taste, his tongue to conceive, nor his heart to report, what my dream was” (cf. 1 Corinthians 2:9).

Shakespeare captures in this dreamworld the aberrant passage of time, inexplicable happenings, strange sensations, and outlandish memories so common in the most ordinary of reveries. We, too, have dreamed and in our dreams seen things “past the wit of man to say” (Act IV, Scene 1).

In the end it may be superfluous for Puck to entice the audience to join in the dreamy midsummer madness:

If we shadows have offended,

Think but this (and all is mended)

That you have but slumbered here,

While these Visions did appear.

In Midsummer Night’s Dream, Shakespeare pulls out all the theatrical stops. He deftly uses entertainment to evoke emotion, understanding, and reflection—and therein lies pure theatre magic.

No responses yet. Leave one!

Posted July 11th, 2013 by Yorick

Abbess. The duke, my husband and my children both,

Abbess. The duke, my husband and my children both,

And you the calendars of their nativity,

Go to a gossip’s feast, and go with me;

After so long grief, such festivity!

Duke. With all my heart, I’ll gossip at this feast.

In Act V, Scene 1, of Comedy of Errors, Abbess Amelia summons the entire company to “a gossips’ feast.” Today’s audiences assume that the abbess is asking them to accompany her for a time of joyful revel and idle chat about the day’s strange goings-on. However, a bit of research into the term reveals a slightly different agenda.

Our word gossip derives from the Saxon word godsibb, which is a combination of God + sib (relative or sibling). The word meant “one acting as a sponsor at a baptism,” and its earliest recorded use as a noun appears in 1014 according to the Oxford English Dictionary. It appears in a sermon by Wulfstan, an early English bishop, who decries the idea of betraying family bonds: “And godsibbas and godbearn to fela man forspilde wide gynde pas peode.” (That’s Old English, folks. Never let it be said that Shakespeare wrote in that!)

In 1605 Richard Verstegan recorded that “our Christian ancestors, understanding a spiritual affinity to grow between the parents and such as undertooke for the child at baptism, called each other by the name of godsib, which is as much as to say that they were sib together, that is, of kin together through God.”

The gossip’s feast that Amelia mentions had a long tradition in medieval England. Such a dinner was typically held in honor of those involved in a christening celebration. This feasting custom is frequently mentioned by writers of the Elizabethan age and beyond.

Shakespeare uses a similar term in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, written sometime between 1590-1596. In the play the impish Puck says:

“Sometime lurk I in a gossip’s bowl,

In very likeness of a roasted crab,

And when she drinks, against her lips I bob

And on her wither’d dewlap pour the ale.”

The phrase “gossip’s bowl” appears again in Romeo and Juliet when Capulet tells the Nurse:

Peace, you mumbling fool!

Utter your gravity o’er a gossip’s bowl;

For here we need it not.

Shakespeare coined the verb form of gossip in 1590 when he used the term in Comedy: “With all my heart I’ll gossip at this feast,” declares the Duke of Ephesus. The Bard used the verb form again in 1601 in All’s Well that Ends Well: “There shall your master have a thousand loves, a world of pretty, fond, adoptious Christendoms, that blinking Cupid gossips.”

It wasn’t until 1627 that scholars find the word gossip recorded as meaning “to talk frivolously about other people and their business.” And the rest, as everyone says, is history. Perhaps all that fellowshipping with one’s relatives got out of hand—the guests ran out of things to talk with each other about and started talking about each. Probably a lot like today’s family reunions.

No responses yet. Leave one!

Posted June 28th, 2013 by Yorick

Problem: What to with two sets of identical twins running about the city of Ephesus in a production in which the actors involved looking nothing alike?

Solution: Outfit them with distinctive eyewear, of course! For this year’s Summer Shakespeare production, Comedy of Errors: The Amazing One-Joke Play, director Jeffrey Stegall decided that glasses would be the perfect choice to convey the twin relationships. This design choice quickly spread to other characters in the show. Take a close look, and you’ll find they establish or enhance qualities of each character: bold, quirky, or nerdy. Pair that with all the striking colors in the costumes—including some wild and crazy nun’s habit fabric from Mood Fabrics in NYC—and even the starkest black frames pop. (In the picture at left, Antipholi Philip Eoute and Johnathan Schofield rehearse with their production glasses on; at right, a selection of eyewear for the choosing.)

Finding the right look in eyeglasses is quite personal. Actors try on and sometimes rehearse in the glasses before deciding upon the perfect pair. Once a pair is chosen, the lenses are usually removed both to eliminate any vision correction that would blur the sight of the actor and to get rid of glass glare for the audience.

So when you come to watch the show, keep an eye out. Who knows? This production of Comedy just may prove to be a spectacle the likes of which you haven’t seen before! (by GSC intern Meagan Ingersoll)

No responses yet. Leave one!

Posted June 18th, 2013 by Yorick

Last week (June 10-14) was filled with many exciting moments as the Greenville Shakespeare Company held our third year of Acting Up with Shakespeare Camp in partnership with Piano Central Studios. The week catered to eager young performers between the ages of 8 and 12 and was staffed by current GSC cast and crew. GSC president/camp director Jeffrey Stegall, actor/musician Nikki Eoute, actor/interns Meagan Ingersoll and Brooke Waters, and cupcake wench Margaret Stegall filled the students’ week with text work, music & singing, drama games, basic stage combat techniques, and even a few Shakespearean insults. (Try telling someone, “Thy breath stinks with eating toasted cheese” or “Thou frothy hedge-born boar-pig!”) In just 4 ½ days students memorized several shortened scenes from Shakespeare’s Comedy of Errors (the play Summer Shakespeare is performing this season), learned choreography to a Comedy of Errors-themed song, as well as practiced a few sword-fighting maneuvers—made more realistic by the hurling of aforementioned insults during the thrusts and parries. At the end of the week, students donned zany costumes (in true Summer Shakespeare style) and performed for parents, grandparents, and friends. It was a perfect showcase of what these creative and energetic students had learned throughout the week. If you have children ages 8-12, we’d love to have them join us next year! (by GSC intern Brooke Waters)

Last week (June 10-14) was filled with many exciting moments as the Greenville Shakespeare Company held our third year of Acting Up with Shakespeare Camp in partnership with Piano Central Studios. The week catered to eager young performers between the ages of 8 and 12 and was staffed by current GSC cast and crew. GSC president/camp director Jeffrey Stegall, actor/musician Nikki Eoute, actor/interns Meagan Ingersoll and Brooke Waters, and cupcake wench Margaret Stegall filled the students’ week with text work, music & singing, drama games, basic stage combat techniques, and even a few Shakespearean insults. (Try telling someone, “Thy breath stinks with eating toasted cheese” or “Thou frothy hedge-born boar-pig!”) In just 4 ½ days students memorized several shortened scenes from Shakespeare’s Comedy of Errors (the play Summer Shakespeare is performing this season), learned choreography to a Comedy of Errors-themed song, as well as practiced a few sword-fighting maneuvers—made more realistic by the hurling of aforementioned insults during the thrusts and parries. At the end of the week, students donned zany costumes (in true Summer Shakespeare style) and performed for parents, grandparents, and friends. It was a perfect showcase of what these creative and energetic students had learned throughout the week. If you have children ages 8-12, we’d love to have them join us next year! (by GSC intern Brooke Waters)

No responses yet. Leave one!

Devious Duke Frederick has usurped the kingdom of his older brother, Duke Senior, Duke Senior’s daughter Rosalind is allowed to remain at court—since she is the treasured confidante of Frederick’s only child, Celia.

Devious Duke Frederick has usurped the kingdom of his older brother, Duke Senior, Duke Senior’s daughter Rosalind is allowed to remain at court—since she is the treasured confidante of Frederick’s only child, Celia.